The BBC

The BBCTurkish airstrikes have cut off electricity and water for more than a million people in famine-stricken northeastern Syria, in what experts say may be a violation of international law.

According to data collected by the BBC World Service, Turkey carried out more than 100 attacks on oil fields, gas installations and power stations in the Kurdish-held Autonomous Administration of Northern and Eastern Syria (AANES) between October 2019 and January 2024. have done

The attacks have added to the humanitarian crisis in a region that has been exacerbated by climate change after years of civil war and four years of severe drought.

Water was already in short supply, but attacks on electricity infrastructure in October last year knocked out power at the region’s main water station, Alok, and it has been out of service since then. On two visits there, the BBC saw people struggling to get water.

Turkey said it had targeted the “sources of income and capabilities” of Kurdish separatist groups it considers terrorists.

It is common knowledge that there was drought in the area, he said, adding that poor water management and neglect of infrastructure had worsened the situation.

AANES has previously accused Turkey of trying to “destroy the existence of our people”.

More than a million people in Haskeh province, who once received water from Aluk, now rely on water deliveries pumped from about 12 miles (20 km) away.

Hundreds of deliveries are made by tanker every day, with Waterboard giving priority to schools, orphanages, hospitals and the most needy.

But delivery is not enough for everyone.

In the city of Haske, the BBC saw people waiting for tankers, pleading with drivers for water. “Water is more valuable than gold here,” said Ahmad Al-Ahmad, a tanker driver. “People need more water. They just want you to give them water.”

Some admitted they fought over it and one woman threatened: “If he [the tanker driver] Don’t give me water, I’ll puncture his tires.

“Let me tell you frankly, northeast Syria is facing a humanitarian catastrophe,” said Yahya Ahmed, co-director of the City Water Board.

People living in the region are caught not only in Syria’s ongoing civil war, but also in conflict with Turkey’s Kurdish-led forces, which after establishing AANES in 2018 – with the support of a US-led coalition – launched an Islamic offensive. Drive the State (IS) group out of the region. Coalition forces are still stationed there to prevent a resurgence of IS.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has described AANES – which is not officially recognized by the international community – as a “terrorist state” along its border.

The Turkish government views the Kurdish militia, which dominates the main military force there, as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) rebel group, which has been fighting for Kurdish autonomy in Turkey for decades.

The PKK has been designated as a terrorist organization by Turkey, the European Union, the United Kingdom and the United States.

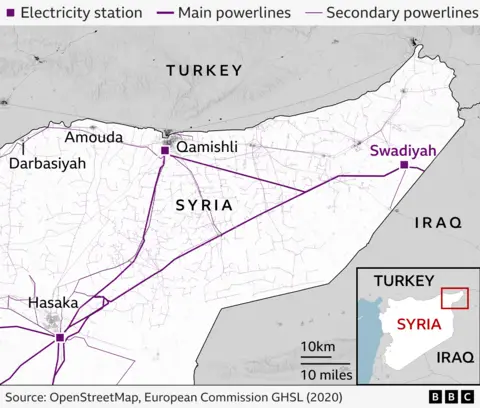

Between October 2023 and January 2024, power transmission stations in three AANES regions were targeted: Amuda, Qamishli, and Darbasiya, as well as the region’s main power plant, Swadia.

The BBC confirmed the damage through satellite images, eyewitness videos, news reports and site visits.

Satellite images of nighttime lights before and after the January 2024 attacks indicated widespread power outages. “On January 18…a significant blackout is evident in the region,” said Ranje Shrestha, a NASA scientist who reviewed the image.

The United Nations says Turkish forces carried out the attacks in Swadiya, Amuda and Qamishli, while humanitarian groups say Turkey was behind the attack in Darbasiya.

Turkey said it was targeting the PKK, the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD).

The YPG is the largest militia in the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces and is the military wing of the PYD, the main political party of AANES.

“Citizens or urban infrastructure are not and have never been among our targets,” Turkey said in a statement to the BBC.

But in October last year, the country’s foreign minister, Hakan Fidan, said that all “infrastructure, superstructure and energy facilities” belonging to the PKK and the YPG – particularly in Iraq and Syria – would be seized by its army, security forces. and are “legitimate targets” for intelligence. Units

The consequences of conflict are exacerbated by climate change.

Since 2020, an extreme and unusual agricultural drought has gripped northeastern Syria and parts of Iraq.

According to European Climate Data, average temperatures in the Tigris and Euphrates basin have risen by 2C (36F) over the past 70 years.

The Khabur Darya once supplied water to Haske, but the level became too low and people were forced to turn to the Alok water station.

But in 2019, Turkey took control of the Ras al-Ain region, where Aluk is located, saying it needed to establish a “safe zone” to protect the country from terrorist attacks.

Two years later, the United Nations expressed concern over repeated disruptions in water supplies from Aluk to northeastern Syria, saying that water supplies had been disrupted at least 19 times.

And a report published by an independent UN commission in February 2024 said the October 2023 attacks on electricity infrastructure could amount to war crimes because they deprived civilians of access to water. .

The BBC shared its findings with international lawyers.

“Turkey’s attacks on energy infrastructure have had a devastating impact on civilians,” said Arif Ibrahim, a barrister at Doty Street Chambers, adding: “This could be a serious violation of international law.”

Patrick Crocker, an international criminal lawyer at the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, said “the indications of a violation of international law here are so strong that they should be investigated by the prosecutor”.

The Turkish government said it “fully respects international law”, adding that a February 2024 UN report provided “no concrete evidence” for its “baseless allegations”.

He blamed the region’s water shortages on climate change and the maintenance of a “long-neglected water infrastructure” there.

Residents of Haske told the BBC they felt abandoned.

Usman Gudu, head of water testing at the water board, said: “We have sacrificed a lot – many of us have died in the war. But no one comes to save us. We are only asking for drinking water.”

Additional reporting by Ahmed Noor and Erwan Rewalt