Pawan Kumar

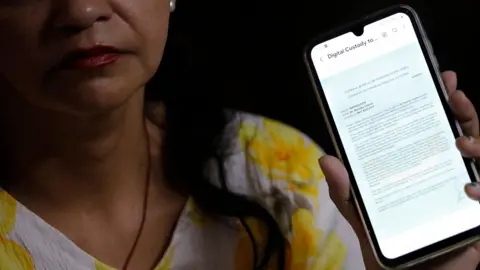

Pawan KumarFor one harrowing week in August, Ruchika Tandon, a 44-year-old neurologist at one of India’s top hospitals, is caught up in what feels like a high-profile federal criminal investigation.

Still, it was an elaborate scam — a web of fraud spread by scammers who manipulated her every move and drained her and her family’s life savings.

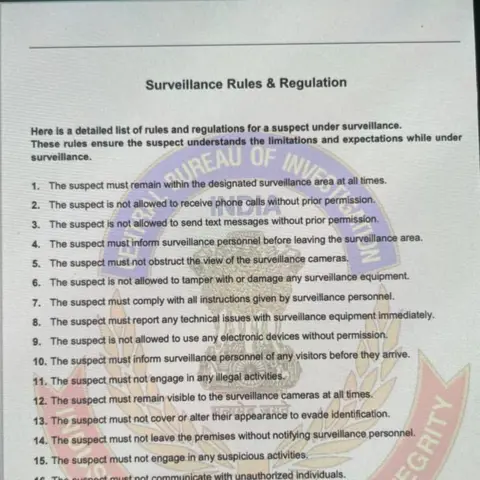

Under the pretense of “digital arrest” — a term coined by his perpetrators — Dr. Tandon was forced to take time off work, surrender his everyday liberties, and obey the non-stop surveillance and instructions of strangers over the phone. had gone, who assured him that he was there. The focus of a serious investigation.

The “digital arrest” scam involves fraudsters impersonating law enforcement officials on video calls, threatening victims with arrest on trumped-up charges, and pressuring them to transfer large sums of money.

In Dr Tandon’s case, they stripped him and his family of around 25 million rupees ($300,000; £235,000) from bank accounts, mutual funds, pension funds, and life insurance – a manufactured nightmare. Years of savings.

She is not alone. According to official data, between January and April this year, Indians lost over Rs 1,200 million to the “digital capture” scam. These statistics only scratch the surface, as many victims do not report such crimes. The stolen funds are often transferred to overseas accounts or cryptocurrency wallets. More than 40 percent of the scams are found in Myanmar. Cambodia, and Laos, according to officials.

Mansi Thapliyal

Mansi ThapliyalThe situation is so bad that even Prime Minister Narendra Modi Talk about a scam In his monthly radio talk in October.

He said that whenever you receive such a call, don’t panic.

India faces a gamut of cyber crimes from fraudulent investment and trade to dating scams. But the “digital capture” scam stands out as particularly pervasive and terrifying—carefully planned, relentless, and invasive to every part of a victim’s life.

Sometimes scammers reveal themselves during video calls, while other times they stay hidden by relying entirely on audio. The plot could be straight out of an exotic Bollywood thriller – except it’s carefully choreographed.

On the dreaded first day, Lucknow-based Dr Tandon was contacted by scammers posing as officials from India’s telecom regulator, claiming that his number had been disconnected due to “22 complaints” of harassing messages sent to him. will go

Moments later, a man claiming to be a senior police officer took over. She accused him of using a joint bank account with his mother to withdraw money for trafficking women and children.

Pawan Kumar

Pawan KumarIn the background, a shrill chorus of voices rang out, “Arrest him, arrest him!”

“The police will come to arrest you in five minutes. All the police stations have been alerted,” the man warned.

“I was angry and frustrated. I kept saying this can’t be true,” recalls Dr. Tandon.

The officer seemed lenient, but with a catch. He said India’s federal spy agency, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), would take over as it was a “matter of national secrecy”.

“I will try to talk and convince them not to put you in physical custody. But you have to be in digital custody,” he insisted.

Dr. Tandon used a feature phone that lacked video calling, making it impossible for scammers to proceed. So they made him go to a store and buy a smartphone.

Over the next six days, three men and a woman, posing as police officers and a judge, kept him under constant surveillance over Skype, his phone camera rolling nonstop.

They forced him to wake up his students at night to buy extra data packs to keep the scam going. He needed to have a phone around the house — while cooking, sleeping, and even outside the bathroom — monitoring his every move.

Mansi Thapliyal

Mansi ThapliyalShe was also forced to lie to her hospital and relatives, claiming she was too sick to work or see anyone. When an uncle went there, they ordered him to hide under a bed with a phone camera running.

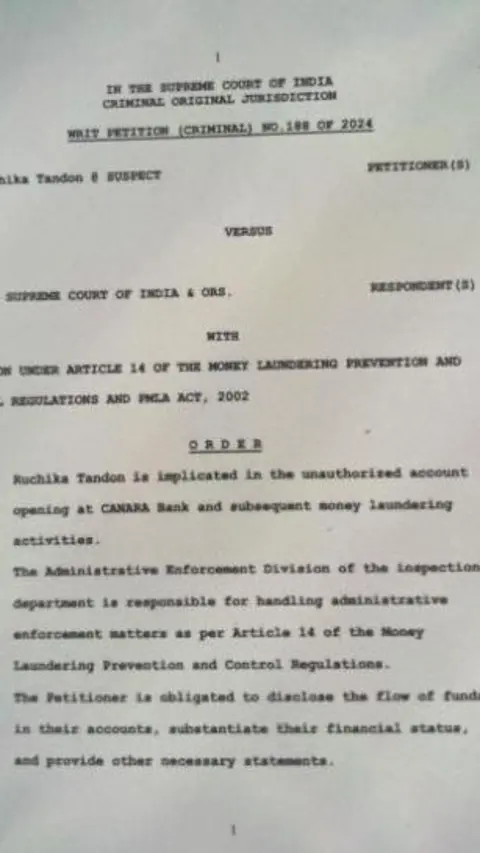

For an entire week, Dr. Tandon endured more than 700 questions about his life and work, a staged trial, falsified court documents, and promises of a digital “bail” in exchange for saving his life. At the mock court she was ordered to wear white to “respect the judge”. The callers had their video turned off, leaving only their fake names and authentic-looking badges displayed on blank screens.

At one point, during the ordeal, the fraudsters even spoke to Dr Tandon’s 70-year-old mother, urging her to keep quiet “for the sake of her daughter”.

As the doctor repeatedly broke down on camera, the fraudsters told him: “Take a deep breath and relax. You didn’t kill. You just laundered money.”

In a desperate bid for freedom, he transferred his entire savings from half a dozen different bank accounts to accounts controlled by the scammers, believing it would be returned after “official verification.” Instead, she lost everything. The callers disconnected the line. After the transfer is complete.

Pawan Kumar

Pawan KumarReturning to work after a week, exhaustion prompted Dr. Tandon to search the Internet for terms like “digital custody” and “new methods of CBI investigation”.

This led to newspaper reports detailing similar “digital capture” scams across the country. She still refused to accept that she was the victim of an elaborate hoax, and she arrived at the police station, hoping that “the police station and the officers are real”.

Dr. Tandon says that he reached the police station anxious.

“I’ve been getting strange calls for days.” She tried to explain.

Before she could say more, a female officer interrupted sharply, “Have you transferred any money?”

At another police station, “when they heard my case, they started laughing”, recalls Dr Tandon.

A police official said that it is now very common.

Mansi Thapliyal

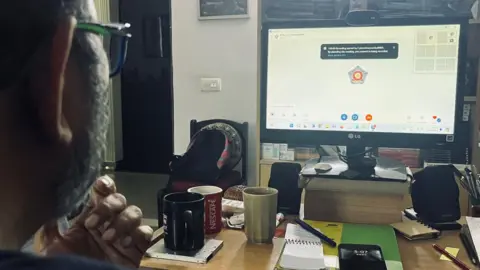

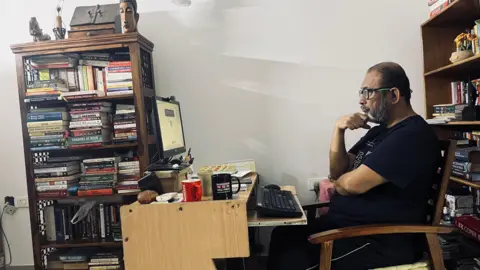

Mansi ThapliyalMore than 500 kilometers (310 miles) away in Delhi, author and journalist Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay narrowly escaped the scandal in July.

He endured 28 hours under “digital arrest” as scammers claimed his defunct bank account was used to launder money. Mr Mukhopadhyay’s suspicions were raised when a caller asked him why he had not redeemed his mutual funds – not a question a police officer would normally ask over the phone.

Mr. Mukhopadhyay slipped out of his study, where the scammers were monitoring him at his desktop, and spoke briefly with his wife. The friends, alerted by his message, told him to quickly disconnect his modem, freeing him from their grasp.

“I became a digital slave until my friends exposed the scam,” says Mr. Mukhopadhyay. “I had my funds transferred to my account, all ready to be transferred to them. I felt like an idiot when it was gone.”

Pawan Kumar

Pawan KumarProgress in catching these fraudsters is still unclear, with many victims frustrated by the slow complaint process.

However, Dr. Tandon has seen some success: Police have arrested 18 suspects, including a woman, from across India. About one-third of the stolen cash has been recovered and deposited into various bank accounts. He has so far received only Rs 1.2 million of the Rs 25 million he looted – that was in cash.

Investigating officer Deepak Kumar Singh says that the fraudsters were running an elaborate operation.

Mr Singh, a senior police official, told the BBC, “The liars are well-educated men and women – fluent in English and various Indian languages - including engineering graduates, cyber security experts, and banking professionals. Most of the Telegram channels work through,” Mr Singh told the BBC.

Investigators believe the fraudsters were clever, using targeted information from their victims’ social media.

“They track you, collect personal information, and identify your vulnerabilities,” says Mr. Singh. “They then quickly attack potential victims using a hit-and-run approach.”

The fraudsters knew that Mr Mukhopadhyay was a journalist and writer – the author of a biography on Prime Minister Modi. He knew that Dr Tandon was a doctor and had attended a conference in Goa. They had their biometric national identification numbers. Mr Mukhopadhyay wonders if he knew he was among the journalists who owned the house. raided In October 2023, as part of an investigation into the funding of NewsClick by the Delhi Police (critics called the move an attack on press freedom, which the government denied).

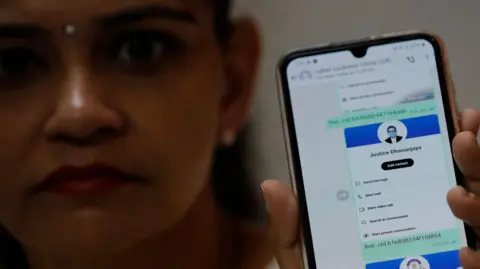

They also made mistakes. Mr. Mukhopadhyay’s caller was unaware of how long it usually takes to redeem funds, raising his suspicions. Dr. Tandon’s fake judge called himself Judge Dhananjay and displayed a fake badge with a picture of recently retired Chief Justice Dhananjay Chandrachud. Yet, overwhelmed by the moment, she lost track.

Dr. Tandon says she still lives in a haze, struggling to separate reality from the nightmare that overtook her life. Even when he filed a police complaint, he wondered, “Was the police station fake?”

Every phone call brings fresh anxiety.

“At work, I sometimes go blank, full of fear. The days are better, but after the evening, it becomes difficult. I have nightmares.”