Photo-Illustration: New York Magazine, Photos: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

Back when the artist Lisa Yuskavage was trying to figure out why her work was making her so miserable, she realized that the women in her paintings were all facing the wrong way.

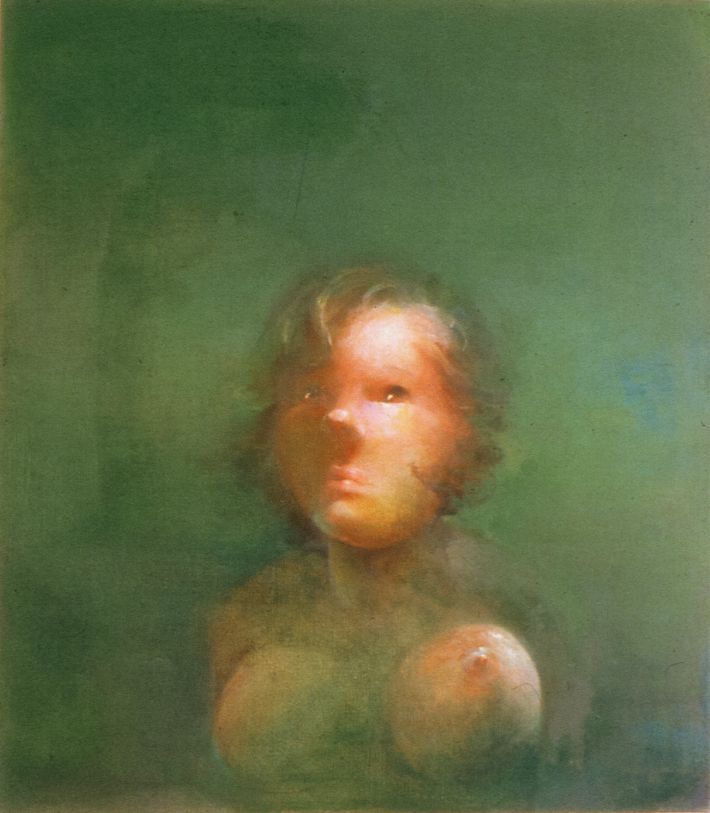

Sweet Thing, 1990

Art: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“Those paintings were mostly about backs,” she said to me. “And I thought, Why are they turned away? What are you hiding? Maybe you’re hiding their big tits. I decided to do the opposite of everything I’d ever done.”

She would get to those tits, but she began with the eyes. “The first thing I did, I painted her eyes, so that she was looking at you, locking eyes with you,” Yuskavage says. “You’re fucked up and I’m watching you. With every new painting at the time, I started with the eyes.”

The Ones That Shouldn’t: Smacked Ass, 1991

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“They were using whatever powers they had to get back at you,” she said. “It’s gonna hurt you as much as it hurts them to be looked at. I wanted the viewer to be a little turned on, and then uncomfortable.”

We were in her enormous studio in Gowanus, in a slice of the neighborhood that resembles the working-class Philadelphia streets she grew up on. Yuskavage is confrontational in her work, but gentle in person, eager to explain why she does what she does. I have always been drawn to her paintings, though I couldn’t have told you exactly why. There is the obvious — the outrageous content, including those perky breasts, present in nearly every picture. And the virtuoustic painting itself — her extraordinary command of light especially. But in fact, as Yuskavage and I talked, I realized it was the eyes that kept me looking, even more than the boobs. How can such an innocent gaze be so provocative? And yet it is.

Yuskavage spends a lot of time staring down what she has applied to her canvas. All painters do, but with her, this “noticing,” a word she comes back to over and over, is particularly crucial. She is hypersensitive to what is working and not.

After she graduated from the Yale School of Art, she assembled all the work she had made. “I had a light table. I laid out all the slides of my paintings and removed everything that sucked. I free-associated what they had in common. And then I took the words that kept showing up: light, luminosity of color particularly. Light is the subject of my work.”

In her case, subject and subject matter are inseparable. The naked young figures that became her protagonists were nowhere present when she began her art career, and they too emerged from clocking her own reactions. She has a useful capacity to be highly emotional and analytical at the same time. Her response is visceral, but leads her to action.

Nowhere was that more extreme than after her first professional art show. It is a foundational story for her, the one that led to making the sort of paintings that have been her signature throughout her spectacular career. She had been making the paintings she felt everyone wanted her to paint, and she had convinced herself that they were pretty good. “I walked into the opening,” she said. “You’re all dressed up. Everybody shows up, everybody’s excited. There’s going to be a dinner afterward. But I could barely get through the evening. I said to my husband, ‘Oh my God, I hate this, I hate it.” I said, ‘Where am I in this? Who made these paintings?’ They’re so uptight and precious and trying to prove something. I said, ‘I need to get the fuck out of here.’”

The paintings were actually beautiful — her painting talent is such that she is probably incapable of making an unlovely image — but something was upsetting her, and she diagnosed what it was. She had grown up working-class Catholic in Philadelphia and was hardly typical of her fellow students at art school: “I was missing my origin story. I was ashamed of it. I had removed any sign of it from my work. I sold some paintings, but they were missing a life force that would keep me wanting to do this the rest of my life. I felt very trashy there. My trashy personality — I have volumes of it.”

Yuskavage knew she had to make a dramatic turn. She had to reject much of what she’d learned in school, maybe not be an artist at all. She fell into a tortuous depression. That was 1990. Eventually, after some struggle, she turned her figures around to face the viewer, and what would come to be the “recipe” (her term) started to emerge: one that integrated her “trashiness” with her love of light, and themes she had been circling all her life without quite registering it.

Central to them was sexuality. As a young girl, she was maybe a little more sexually curious than most but certainly precocious in being attuned to the ways it can turn dark. She found porn, and was fascinated by it. And she began to notice little signs of abuse around her.

She’d had a best friend who’d been molested. “When she told me what was happening to her, I cried and cried and she sat there dry-eyed. And I realized later she’s the person who taught me empathy. People think I am the molested person. Well, there is a molested person in the mix here. But if I had been her, I could not have created this work”

The friend became the archetype of the girls who appear ubiquitously in Yuskavage’s work — the helium-titted animelike figures that are, she says, “my children.” “In a way she created my imagination,” said Yuskavage. “She originated certain thoughts” — especially around vulnerability. Yuskavage’s “children” have grown-up bodies and little-girl faces. In a sense they are all set in a pubescent world.

“In puberty, you’re becoming sexual but you’re not ready to get fucked. What puberty was like reminded me of what my paintings were like — they didn’t want to be seen. My paintings were like pubescent girls. They wanted to hide, but they couldn’t hide. So when I turned them around, they had these attributes that were extremely sexualized, but they had these childlike heads. And then their eyes were looking at you.”

From this idea came a torrent of work — a series called “Bad Babies”; then another called “Bad Habits,” paintings of Sculpey sculptures she had made; then paintings drawn from images in Penthouse and live models. “The early work was where I was really cooking with gas, in the early ’90s. I was connecting, figuring shit out.”

Most were painted in loud, garish colors — putrid green, neon yellow — unusual in contemporary painting. Color, she felt, denoted class, and she wanted to embrace the crassness of where she’d come from. Her palette was more confrontation, another way of flipping the bird at her viewers. “It’s this Barbie-doll kind of aesthetic, a world of artifice. This is not the world of Leonardo. Leonardo didn’t have hot-pink paint. And if he did I don’t know what he would have done with it.”

The paintings weren’t immediately accepted — in fact they were reviled, mostly as anti-feminist, the obverse of what she intended. “I wanted to tell the truth about something gnarly. I had never seen a painting that included a kind of vulgar experience of being a female. My work was really hated. And then people were intrigued. I took a lot of shit for it, but it was okay. I was like, All right, I’m just going to make it more fucked up. Now I’m going to bring a pussy in — a bald fat pussy. But make it the most beautiful thing ever.”

I had come to Yuskavage’s studio to discuss the evolution of a single painting of hers, called Painter Painting. It’s in a show that recently opened in Los Angeles. Like most of her later work, it’s also about all her work, over the years.

“Somebody might say, ‘How long does it take you to make a painting?’ I say, ‘Well, where are we starting?’” She is 62 now and enthralled by a productive rush — her peak, she thinks, making paintings that “put it all together.” This show, like her last, is made up of what are known as “studio paintings” — that is, paintings set in an artist’s space, often with the artist in it. There is a long tradition of studio painting in art — Courbet, Matisse — but most painters make one in this genre and then tack in another direction. Not Yuskavage. This isn’t a phase; it is her work now. On Yuskavage’s website, you will find 41 paintings under the keyword “studio.” (You will also find 16 paintings by clicking “masturbating.”)

Before Yuskavage and I sat down to talk about Painter Painting, we first wandered around her studio. It’s airplane-hangar huge, divided into three rooms. The first is an office. On a table were several drawings she made over the years that were to be included in a show at the Morgan in New York in June, some of which she found recently as her work was being digitally archived. There were two drawings of a girl without pants.

We were talking generally about where her work comes from — it is inevitable when work is as loaded as hers. “There is no smoking gun,” she said. “It’s lots of things. You have to be an irreverent person in some way. Be Catholic but not. Have to have a certain kind of training and then you shit on that training. And then are you willing to do this? Reject the hand that feeds you?”

We were looking at the table. “I had another friend, who was my roommate in school. She had sex with every guy in our class, and I had to hear it and, man, that girl could pop pretty good. It was like boom, boom, boom. She would walk around with a T-shirt on and no pants. She had a huge bush and a cute body, but it was like, Do I really need to see this all day?”

This sounded to me like a detour — Yuskavage is full of detours; she is a voluminous, digressive talker — but it wasn’t at all. During the same period, she made a drawing of the same girl in ballpoint pen, which she’d also recently found.

Untitled (notebook drawing), 1989

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“My roommate must have been on my mind. I made that scratchy drawing when I was still making more reticent work. I literally just took out a ballpoint pen and started drawing her. It was me thinking about something I wasn’t brave enough to do for another two years.”

Also on the table was a drawing of one of the Bad Habits sculptures, called Motherfucker.

A 1995 photograph of one of her Bad Habits sculptural maquettes, “The Motherfucker.”

Art: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

They would both play featured roles in Painter Painting.

We passed through a room she calls the Drawing Room — most of her work begins in drawing, where she gets what she calls the “little monsters” out of her brain — then onto the cavernous space where she paints. You could roller-skate in it. There were acres of opened paint tubes, acres of brushes. Three huge canvases were propped up, covered in ground, or backdrop color, which is crucial because this ground is often a character in her painting, as it would be for Painter Painting. She keeps these canvases around as backups in case she screws up a painting and wants to start over — they give her permission to fail. One had a preliminary drawing in charcoal. She was drawing freehand off a painting she’d already made, a “small painting,” one of several that were on the wall.

Yuskavage is famous for these small paintings. She is an artist of extremes. She goes from the small paintings to super-size paintings (and sometimes the other way around), rarely painting any size in the middle. Some are final works in themselves; many are studies for larger paintings. She tried several times to explain the relationship of the big and small paintings to me and finally arrived at this formulation: “The small paintings spark an idea — doesn’t matter how dumb or seemingly insignificant — I don’t question it and know that I can throw it out without a blink if it’s a false start. When I go to the big ones, it’s with some sort of conceptual clarity of what I want to see and I approach it in a different way. The scale does ask for more planning. I think the small ones might resemble what most people imagine painting to be like — finding things in paint. Whereas I think the larger ones are more like building a house or sculpture. I would miss one without the other. ”

We settled down into two little chairs in this vast space, facing each other. She showed me a new counterweight easel she had bought which would help her paint the bottoms of the canvases without killing her back. The easel held a canvas empty but for the ground. By the time I came back a week later to continue the conversation, it was filled with a giant head of one of her girls and an artist crouching, painting her. A small iteration of this painting was right beside her. At this point, the L.A. show was just around the bend, but she was still coming to the studio every day, ten to seven, or “when the green light is on,” making more work and moving fast.

She is calling the painting Painter Crouching for the time being, and it too is a studio painting. She knows people question why she won’t let go of the studio as a subject, and it clearly rankles her, just as it does when people ask why she continues with her girls.

“People used to say, ‘Why don’t you paint something else besides a girl?’” said Yuskavage. “But I was like, ‘These are my stories. This is what moves me.’”

For her, the studio paintings present nearly infinite possibility. In them she works out versions of herself, revisits her own corpus of work. Flowers are a motif. Birds wander in and out; there’s a stunning large painting on the wall of her studio that isn’t in the L.A. show and that features a peacock — a bird she didn’t know had art-historical significance until she’d already painted it. And then there’s that — art history, her forebears, with whom these paintings are communing.

Which gets in a sense to this room where we are sitting, the setting of all this new work. Outside is hubbub; here it is quiet. She used to have two assistants; now she has none, because the silence is crucial to her. It is where she can notice — and listen. It is not all that different from registering her reaction to her own work. In a sense, the studio is where she can talk to herself.

“Here, there’s a lot of summoning. I see something and then I decide to pull it out. I don’t really think about my subconscious, or of dreams. I think more in terms of seance. It feels very supernatural to me.”

From someone so corporeal, all the woo-woo in how she describes how she paints pictures was a bit surprising to me. It shouldn’t have been — in my talking to other artists of all stripes, I heard over and over again the otherworldly ways they described how their work took hold, because it was such a mystery to them. This translates different ways, depending on the artist. But even with all that, I wasn’t prepared for how seriously she takes the mystical as a partner in her work.

“I don’t want to go down in history as a total fucking flake,” she said. “I realize I’m probably going to go over people’s heads talking about sacred conversations and seances and stuff. But two or three people will get it, that’s fine. Because I don’t always know how I’m doing this. And that’s what the studio is for.

“When I’m walking around, I mostly think about my work, I recognize a problem, I need to get away from it in order to see a problem. And that’s why it’s important not to always be here, to get the fuck away from the summoning where I get intoxicated by what I’m doing.”

But it’s here in the studio where “these little messages will pop into my head. It’s almost like a sexual urge, to do something in a painting.” She told the story of making a picture I like a lot, called Night Classes at the Department of Painting Drawing and Sculpture, looking at it, thinking something was wrong, and feeling nauseous. That urge told her to cover the painting in a red-purple scumble. She did. Then it told her to create a path of light in the painting. She followed the order. Suddenly, the painting worked. Her nausea disappeared.

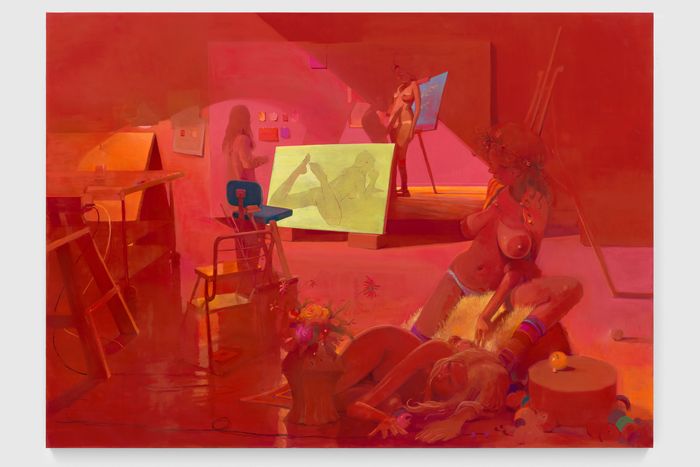

Night Classes at the Department of Painting Drawing and Sculpture, 2018-2020

Art: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“I will take any comers that will lean in and say, ‘Okay this is what you’ve got to do.’ And that’s why what I’m telling you are instructions that I get bit by bit — it’s because I don’t feel there’s any way I could know any of this. I trust it because it’s never failed.”

“I’m not saying the voice is outside me. And it’s true that once I [hear it], then I have something to respond to, and it’s where my painting experience comes in. I know how to create luminosity in a painting.”

“But some of it comes from fucking nowhere, and I’m grateful to be able to hear it. And that’s why you need to be in a studio by yourself.”

So you can understand why she thinks of the studio as sacred, and perhaps why it’s the subject she won’t let go of. But there are other reasons too that have to do with being in her 60s, this stage she is in. “You can’t fake a life. I mean yeah, my tits are sagging and my back is out and I’ve got to do physical therapy but this — this is fire. You’ve got to take advantage of what you’ve got. This is the accumulation of a life of exploration and study.”

This exploration was energized by the digital archive she had recently created — seeing her lifetime of work laid out before her. That’s why in Painter Painting, she brought in Motherfucker, her early drawing, and an important work she calls her “origin painting,” titled Faucet. She made the Motherfucker sculpture working off of the figure she had painted in Faucet — for Yuskavage, all work tumbles into each other.

Faucet, 1995

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

There’s even a prompt from the Night Classes painting you saw above.

But while looking at the archive, she also noticed photographs she’d saved of herself. “And all of a sudden I began to see it all — I have a lot of material,” she said. “And I realized I am material. There’s a whole file in the database of Lisa posing for people in her studio.”

So she found herself ready to put herself — an image of herself as she actually is, in late middle-age — at the center of a painting. That’s what makes this painting so singular: she is the protagonist. It’s probably true what they say — that all work is self-portrait. But here it is the literal truth.

I went to look at Painter Painting at the David Zwirner gallery, where it was sitting en route to the Los Angeles show. It was huge — 94 inches tall — awesome in every sense of the word. It took her over four months — and a lifetime in a sense — but with most of that time just waiting. Noticing.

Lisa Yuskavage: “This photo

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

is an outtake from a photo shoot for the Times that the photographer, Jason Schmidt, shared with me. I thought it was funny. I wasn’t any kind of sexy woman painter. I looked dumpy, almost troll-like. Hard at work wearing glasses.

“I’d had a show, and as I walked around it, I said to the paintings “‘Talk to me, talk to me’ — what is the thread here?” And I kept getting drawn to one painting in particular, Night Classes at the Department of Painting Drawing and Sculpture, asking myself “What is it about this painting that has the oomph?” And I remembered that that painting was in progress when Jason photographed me. He took the picture of me in front of it, pretending to paint the picture. And I just loved the picture. I thought it was funny.

“I went back to my studio and looked at the picture, and I literally just decided to paint myself from that photograph, which is not something I normally do. First I had to ask myself, Now what else is in that studio? I had to figure it out. I wanted to paint a painting inside the painting with me painting it. So that’s what I did in a painting called Flesh Studio.

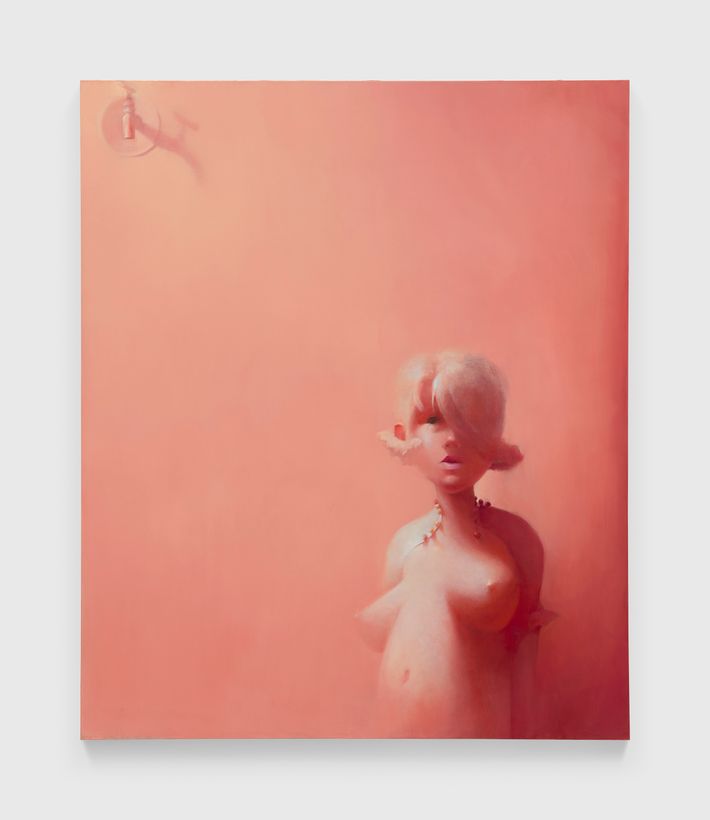

Big Flesh Studio, 2022

Art: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“The question I get asked a lot is, “When are you going to put yourself into a picture?” That was the first time. But I was sort of timid about it. I’m very subsumed — I’m red and you don’t see me.

“In Flesh Studio, I was kind of hidden. And then I thought, Well, let me own this a bit more and kind of pull it forward. So this painting we’re talking about, Painter Painting, was an experiment in trying to figure that out. The idea was how do I reapproach the troll-looking girl.

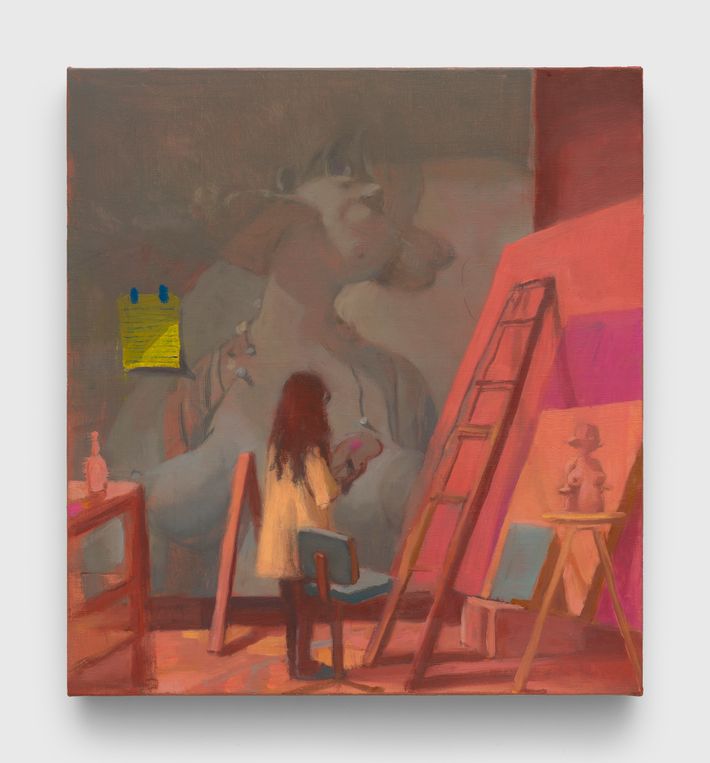

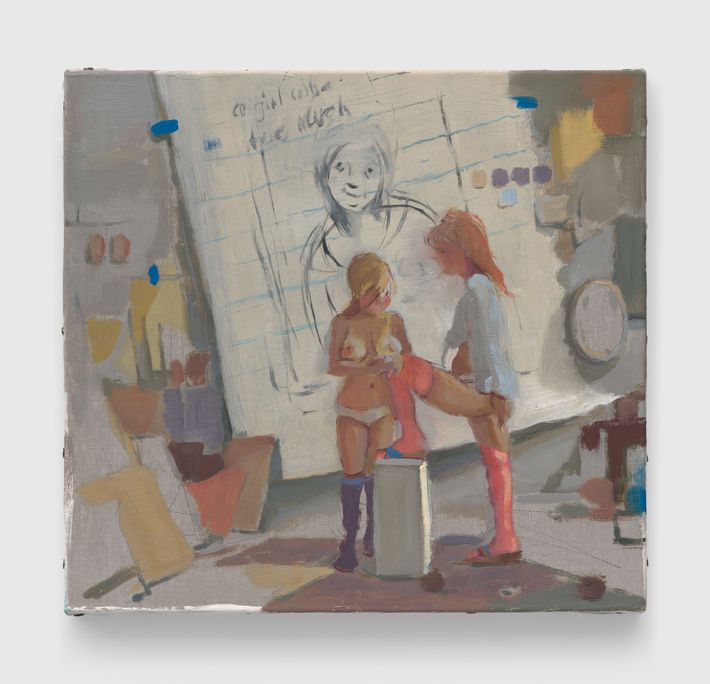

“So I painted a small painting.

Painter, 2024

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“In this painting, the artist is dwarfed by these big tits. The tits come from a drawing I had made of one of my earlier “Bad Habits’ sculptures, Motherfucker. You saw it in the other room.

“And in the small painting, I’m making a painting from that drawing. I’d had it floating in my studio — a photo of it.

“And the small painting was good. But I thought to approach the big painting with a different energy. It takes a while of looking and thinking. I wanted to take everything to the extreme.

“One of the big decisions I made was what size canvas. I wanted it big — human scale, like the real scale of a room. The decision was, how big these tits had to be. They had to be really overwhelming in person.

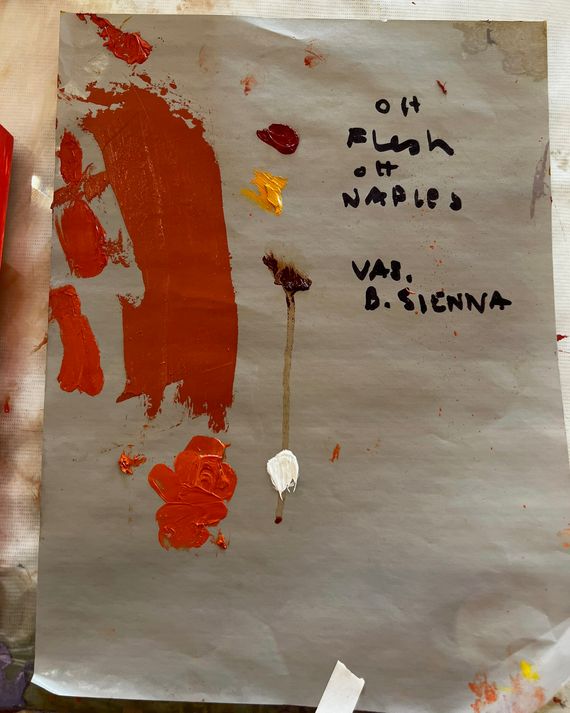

“Now this painting is also a study in color and contrast. I start with the ground.

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“The ground is a mixture of colors. Here’s how I got to that mixture. The size of the swatch is shorthand for me of what percentage of each paint I used: Old Holland flesh ocher and Naples yellow, Vasari burnt sienna and lead white.

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“And I add the drawing on top of the ground.

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

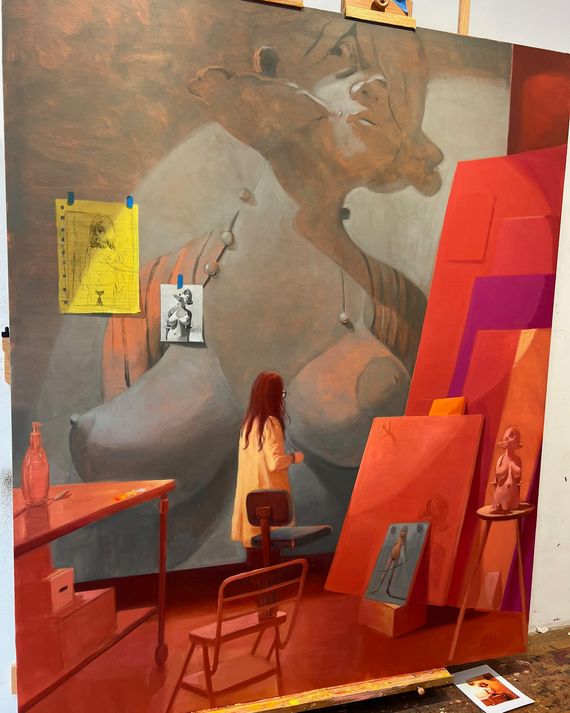

“Here’s the painting, same day, when she’s more developed, I’ve brought in a layer of a gray mixture, and I start putting in [the stuff around her] which I mark with tape because I want really, really sharp edges.

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“And I’ve decided with this big painting to really blow the scale up. I look like a lump, and I really liked that. I like that she’s painting these really obnoxious tits that are unreal. The point is these obnoxious breasts. It’s a scale contrast, a color contrast, and also a contrast of ways of being a painted female. And it speaks to my history.

“And I wanted her to be more dwarfed so that it’s funny and — okay, people say “Who is Lisa? Does she have big tits?” But by setting myself against these giant breasts I’m saying, “No tits and ass here.” It’s all work, which is pretty much the way I am.

“The scale was important. I always think about what is the main thrust of the thing, and then how to make so I don’t beat around the fucking bush, so to speak. It’s another way of saying, what the fuck are you trying to do here, spit it out.

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“I may have projected the drawing to see how big to make her, but I don’t like to project fully because it distorts in a way I don’t like. I go back in freehand because I like what happens in freehand. And this is a contrast not just about size but also about color, because while I’ll be in color, the Motherfucker painting will be grisaille. I like the contrast of the black and white against the color. So then I have to let it dry, 100 percent dry, which probably took two weeks. While it’s drying I’m doing other stuff in the studio so that you’re not tempted to go back and pick the scab.

“Drying is a very big part of this and it’s really fortunate. You get to consider the painting. It allows you time to look it and think.

“And so, when it’s dry, I go back — and it’s a crazy moment —I paint over the whole picture. There was too much contrast — I have to pull it back. I ‘m trying to bring it back together. I don’t think I realized this is going to have to happen, but then I looked at it and I realized this is going to have to happen. When I made the initial ground, I saved a big tube of the color because you can never remix an exact color. So then I took that, thinned it with turpentine and an oil medium, and I put on what’s called a dry wash. I go in there and really work it, wipe away certain areas. I can still see my drawing underneath.

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“Then it sits there, dries, dries, dries. And it really looks like shit. But a painting has to go through some very doggy-dog stages. Otherwise, there’s no raising Lazarus from the dead.

“So then I start putting more information in. The silhouette stops being a silhouette. And then I start painting other things darker. Look how much lighter the ground now looks —it’s even shocking to me, it’s the magic of color, it’s all relative.

“Oh, and see the step stool? It wouldn’t matter to anybody, but I used to sit on a step stool in my grandmother’s kitchen, watching her make spaghetti. It’s — what do they call it in the movies? — an Easter egg.

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“And you see at this point, it looks like this giant work in progress. When I look at this stage, I think it’s fabulous. I could have stopped right there, but I didn’t see it then. I don’t think it was a mistake not to have — but it’s useful for another painting.

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“Now this, it’s almost my favorite stage of the painting, when I bring light in. It’s in an arc — notice this tiny bit of yellow on the canvas where the arc lands? It’s a circle, an ellipse. When I do shit like that, I do a little dance.

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“In the small painting, you may have seen that yellow page I put on the left. I liked the way yellow contrasts with the warmer colors, but I didn’t know how I was going to fill it, and then I saw one of my old drawings — this one done in ballpoint pen — that were sitting around the studio because I’d just found them. I love legal paper. My rational brain needs legal pads. While I was doing this painting, I was working on another one where a notebook page takes up most of the painting.

Notebook (loved too much), 2024

Art: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“Why did I want a gray? It’s to contrast with this yellow rectangle, which I also put in the small painting. And I just brought that idea into this picture.

“Okay, now I’m going to get to what makes this painting really cool. I had noticed I’d taped a picture to the side of the canvas — did you see that in the earlier stages of the paintings? That was real, I was using it as reference to paint the giant Motherfucker. And I thought, What if I paint in the reference picture? I mean, it’s such a wise-guy move. I came in here on a Saturday and I had a plan to do it, and I was like, Okay, it’s going to have to look really different than anything else because it actually has to look mimetic. I’ve never painted a photograph as a mimetic thing in a painting. I decided, Well, it really needs to be sharp-edged, the underpaint needs to be completely dry. I dress-rehearsed it in my mind a thousand times. I had to go to the store to get back paint because I didn’t have any. And then I love the idea of blue tape — but what is the scale of the blue tape — is it a true to life scale? So I did a lot of planning and I came in and did it. First try. And I did it in an hour. And I even said to myself, Good job, you didn’t fuck it up.

“And then I painted Faucet very subtly on the lower right, and I painted this other other picture, Girl With Skewer, of mine [with a scythe.] I had a paintbrush in my hand — so it was like there were two skewers.

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“And then finally I wondered whether I should paint Post-its in there, too, on the canvas. But I thought before I fuck this up, maybe I should paint it on plastic just to see.

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“I tried seeing if it worked, and I had the sense that was this moment I almost took it too far. I was like, Okay, no, I’m out.

“Here’s the finished painting. There’s not an ice cube’s chance in hell that I could make that painting again. I can show you, but it’s so unique and magical — there’s a whole gestalt where my head, my psyche, the world we’re interacting with led to that.

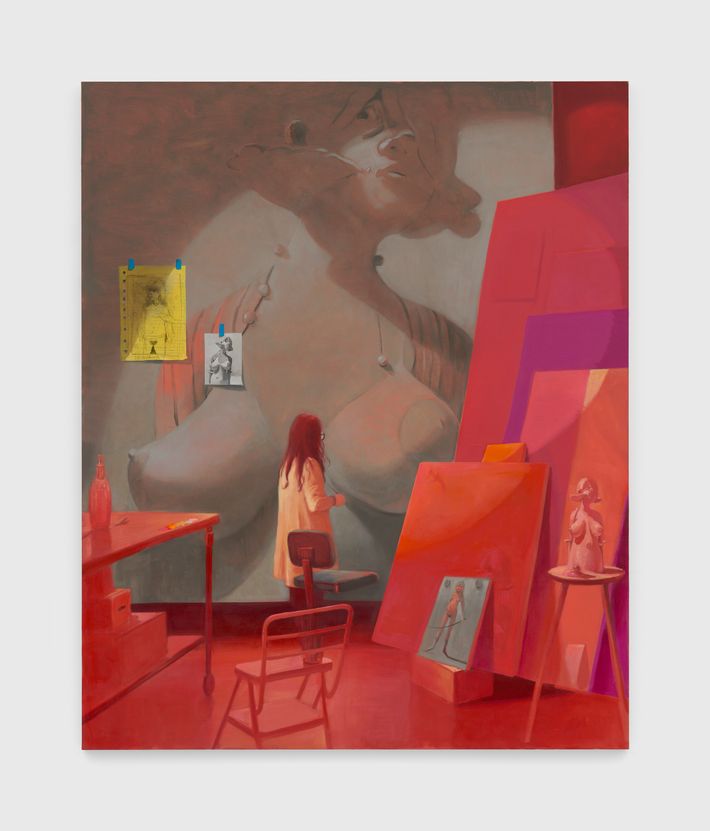

Painter Painting, 2024

Photo: © Lisa Yuskavage, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

“I called it Painter Painting. One of my favorite documentaries of all time is called Painters Painting. It’s from the ’70s, and it’s all men — Jasper Johns, Rauschenberg, Pollock — with their pants up to here. And I know they wouldn’t have taken me seriously at all, and I don’t care. I just love the idea that I can be maybe a little bit of an asshole and assert myself in my own playful way. And that’s what the title was for, right?

When Yuskavage asked me about my own fumbling efforts at painting, I told her that I had been working for weeks on one portrait which was over-worked and dull, and that, in frustration, I crudely, cartoonishly, painted a head in the corner, looking at the main figure. I said I saw that this head, which I painted in three minutes, was a ton better than the one I’d labored over. She nodded vigorously. “So you’re deskilled?” I had never heard that term before. “That’s an advantage. I had no choice. You’re not going to catch up with someone who studied painting for 20 years. It’s those moments that are the most critical in painting when you notice something. Noticing is the summoning to be a good painter. You can’t plow through.” Yuskavage’s mother paints dogs, and Yuskavage said she’s a good painter. “But what my mom does wrong is that she doesn’t notice things. She wants it to look just like the dog. You need to notice things that you didn’t intend that might be smarter than you. You need to take note that something was better. Don’t crush the birdie when the birdie lands. Just squeeze it gently and see what happens.”

Much of the actual time it took to make Painter Painting was watching paint dry. She resisted the temptation to go in and rework the wet paint, which takes a lot of willpower. “Being impatient is a rookie move. And I have done rookie moves and I say, ‘What a rookie move.’”

“If you include that one, you’ll change art students’ lives. For some reason that’s what they tell you to do in art school, but your paint is always dirty.”

If you make a complicated mixture, make a lot more and put it aside in a tube. You’ll probably need it, and it’s nearly impossible to re-create a mixed color.

“I read long ago that art comes from three places: first is the inner life of the artist — the subconscious or whatever. The second is art itself — sculpture, film, paintings — and its history. And the third is points of nature — landscape, the world outside of the art. The way that artists negotiate these three points — inner life, outer life, and other art — which ingredient gets what percentage — makes their recipe. When I look at younger artists, I don’t see enough of other art references, though I question whether I’m being old fogyish about that.”

“I am not crazy about the art world. The artists who I think really love the art world love it, but then there’s that pesky business of making art. I’m very glad I didn’t get a lot of love early. I kept thinking, When is it going to happen? They weren’t buying what I was selling. I never got so much love and attention while I was forming. So I had to keep doubling down believing that I was right, pushing ahead to make it clear. I think that’s why I’m so grateful to the naysayers. The interesting things about the collectors is they want to see the artist develop but at the same time they make it impossible for them to develop because the minute they do — it’s not anybody’s fault. But I worry for those who get early adulation. How do you disappoint?”

Besides being a gifted artist, she is a popular one. Her large work sells for more than $2 million a painting.

Yuskavage had one early collector who loved her work and essentially supported her in her first years as a painter. But when he saw the new kind of paintings she was making, he was repulsed. “He truly believed that I had taken the path to hell. I would say to him, ‘How can it be wrong if I feel for the first time that I can breathe?’”

As I approached her door, a notification lit up my phone saying that David Lynch had died, uncanny timing given how central Lynch is to Yuskavage’s work. When she couldn’t get up the gumption to paint the confrontational paintings she wanted, she went to see Blue Velvet. “I loved that the Dennis Hopper character would sniff, I dunno, nitrous oxide, saying ‘Show me your pussy’ to Isabella Rossellini. And I remember thinking that that was shocking.” Shocking was what she was looking for. So she tried to “enter Frank,” the Hopper character’s head, which freed her to embrace her vulgarity and aggression. “I kind took on a persona of being an asshole,” she said.

Yuskavage thinks of herself as a painting “top.” “It means you’re in charge of how this is going. You have to take command and make very big decisions. Probably more accurately you have to be both bottom and top. But especially when you’re a girl you have to take control. ‘May I enter the art-historical conversation? No? Then fuck it, get the fuck out of the way.’”

She is referring here to one Renaissance painting that particularly affected her: Bellini’s Sacred Conversation. “This was profound in a way that I had never seen. There were all these saints coming in from different parts of history. They did not live at the same time, but I was blown away by the fact that they seemed to be intuiting each other’s

presence without interacting.” This

kind of “sacred conversation” is a big part of most of her later paintings especially, including Painter Painting.

“What I love about this painting,” Yuskavage said, “ is when I was in school everyone used to fuck around in the middle of the night. I mean, literally fuck around, get bored, and start touching each other because we’re kids. So I was kind of trying to convey a moment that I don’t think anyone’s painted before, this weird moment in the middle of the night in art school where everybody gets sick of painting their abstract paintings and starts touching each other and having a great little time.”

One other example: She made a painting called Wilderness. She sold it. Then she stared at it some more. Something bugged her. A voice in her head told her that she had only painted half the painting. She imagined what was to the right of the image she’d made and added a canvas, made it a diptych. “It was funny,” said Yuskavage. “The guy bought it, and then I said ‘wait’ — and I doubled the size.”

While I was visiting Painter Painting at the Zwirner gallery with some of my magazine colleagues, Zwirner wanted us to take a look at another painting sitting on the floor in an anteroom. It was Faucet. Yuskavage and I had been talking about this painting, and it was startling to see it in the flesh. You could see why it was her “origin painting” — a culmination of her search, and the springboard for all that followed. It was low and high at the same time, innocent and wicked, demure and confrontational, suffused in a shimmer that’s like the interior orb of a flame. “Faucet” is being shown at the same time as Painter Painting — at Frieze Los Angeles.

That painting is called Notebook (Loved too much). She painted it from another notebook page she’d recently found from decades ago, on which she’d written “a girl whose father loved her too much.” The two women in it are models she’d picked up at Supper, a restaurant in the East Village. She finds a lot of models there, women who “already look like what I make up.”

An indication of how good Yuskavage’s painting skills are? Pedro Almodóvar, a friend of a friend of Yuskavage’s, was over at the studio when this painting was being made. He tried to lift the notebook page off the canvas. “He was just confused by which one of these objects was fake and which was real. He thought the yellow paper was real.” Also, if you ever have a chance to see this painting in person, just look at the blue tape. It’s a one-inch masterpiece.