TT News Agency/AFP

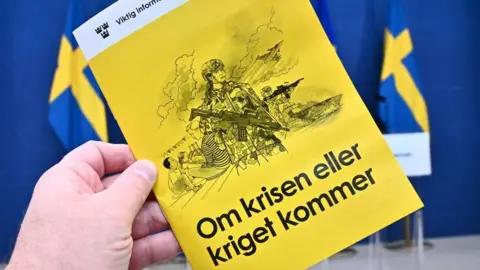

TT News Agency/AFPOn Monday, millions of Swedes will begin receiving copies of a pamphlet advising the population on how to prepare for and deal with war or other unexpected crises.

“In case of crisis or war” has been. Updated from six years ago. Because the government in Stockholm calls the deteriorating security situation, which means a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. The booklet is also double the size.

Neighboring Finland has also published its latest advice online on “incident and crisis preparedness”.

And Norway also recently received a pamphlet. In case of severe weather, war and other threats, he urged to be prepared to manage himself for a week.

In a detailed section on the military conflict, Finland’s digital brochure Explains how the government and president would respond in the event of an armed attack, stressing that the Finnish authorities are “well prepared to defend themselves”.

Sweden joined NATO this year, having decided to apply in 2022, as did Finland after Moscow extended its war. Norway was a founding member of the Western Defense Alliance.

Unlike Sweden and Norway, the Helsinki government has decided not to print a copy for each household because it would “cost millions” and a digital version can be updated more easily.

“We have sent 2.2 million paper copies, one to every household in Norway,” said Tor Komfjörd, responsible for the self-preparedness campaign at Norway’s Directorate for Civil Protection (DSB).

sikkerhverdag.no

sikkerhverdag.noThe list of items to keep at home includes long-life foods such as tins of beans, energy bars and pasta, and medicines including iodine tablets in case of a nuclear accident.

Oslo sent an older version in 2018, but Komfjord said climate change and extreme weather events such as floods and landslides have increased the risks.

For Sweden, the idea of a civil emergency booklet is not new. The first edition of “If War Comes” was produced during World War II and updated during the Cold War.

But a message has been moved up from the middle of the leaflet: “If Sweden is attacked by another country, we will never give in. All information to the effect that resistance is to be ended is false.”

Not so long ago, Finland and Sweden were still neutral states, although their infrastructure and “total defense systems” date back to the Cold War.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSweden’s Minister of Civil Defense, Carl Oskar Bohlen, said last month that as the global landscape has changed, information to Swedish households must also reflect these changes.

Earlier that year he warned that “there could be war in Sweden”, although this was seen as a wake-up call as he felt that progress towards rebuilding “total defence” It’s happening very slowly.

Due to its long border with Russia and its experience of fighting with the Soviet Union in World War II, Finland has always maintained a high level of defense. However, Sweden lost its infrastructure and only in recent years has begun to develop again.

“From Finland’s point of view, it’s a bit strange,” according to Elmari Kihko, associate professor of war studies at the Swedish Defense University. “[Finland] never forgot that war was a possibility, whereas in Sweden, it took a bit of a jolt for people to realize that it could actually happen,” says Kaihko, from Finland.

Melissa Hava Ajosmäki, 24, who is originally from Finland but studies in Gothenburg, says she became more worried when the war broke out in Ukraine. “Now I feel less worried but I still have the thought in the back of my head of what I should do if there is a war. Especially since my family is back in Finland.

The guides include instructions on what to do in a number of scenarios and ask citizens to make sure they can fend for themselves, at least initially, in the event of a crisis.

Finns are asked how they will cope without electricity until the end, with winter temperatures as low as -20C.

Their checklist includes iodine tablets as well as easy-to-cook meals, pet food and a backup power supply.

The Swedish checklist recommends tins of bolognese sauce with potatoes, cabbage, carrots and eggs, and ready-made blueberry and rose soup.

Swedish economist Ingemar Gustafsson, 67, recalls receiving an earlier version of the pamphlet, saying: “I’m not that worried about the whole thing so I take it very calmly. It’s good that we have this. There is information about how we should work and how we should prepare, but it’s not like I’ve done all that preparation at home.

One of the most important recommendations is to have enough food and drinking water for 72 hours.

But Ilmari Kaihko wonders if this is practical for everyone.

“If you have a large family living in a small apartment, where do you hide it?”